What could it mean to decolonize “British Columbia”?

Until we reckon with our history of violence and land theft, B.C. will struggle to solve the big problems we face today.

In the mid-1850s American miners kidnapped Stó:lō children on the Fraser River to use as slaves, many of whom died. Then the prospectors began to shoot men, women and children to clear the riverbanks for gold mining. Those murders helped lay the foundation for the province we call home.

Decolonization is the process of undoing colonization and repairing its many harms. It is a long-term project that involves transferring power, wealth and land back to the people it was taken from. In this part of the world decolonization is still at a very early stage. Many non-Indigenous people are still learning how “British Columbia” was colonized to begin with.

In 1858 the Nlaka’pamux and other interior nations were already panning for gold to trade with the Hudson’s Bay Company at Yale and Fort Hope. And they relied on the same rivers for salmon, which were crucial to winter survival. Indigenous people began to retaliate against the invading prospectors.

That summer, hundreds of American miners organized themselves into armed militias. Led by veterans of the U.S. Indian Wars, they poured across the 49th parallel and embarked on a campaign of extermination. They burned villages, destroyed food caches, lynched, raped and shot people as they marched up the Fraser and Okanagan rivers. [1]

The Nlaka’pamux, Secwepemc and Okanagan gathered a force of thousands of warriors to repel the militias. The U.S. Army assembled 1,500 troops in Washington State, armed with howitzers. Only last-minute peace talks at Lytton between the war chief Sexpinlhemx and a California militia captain, Henry Snyder, prevented a larger war. [2]

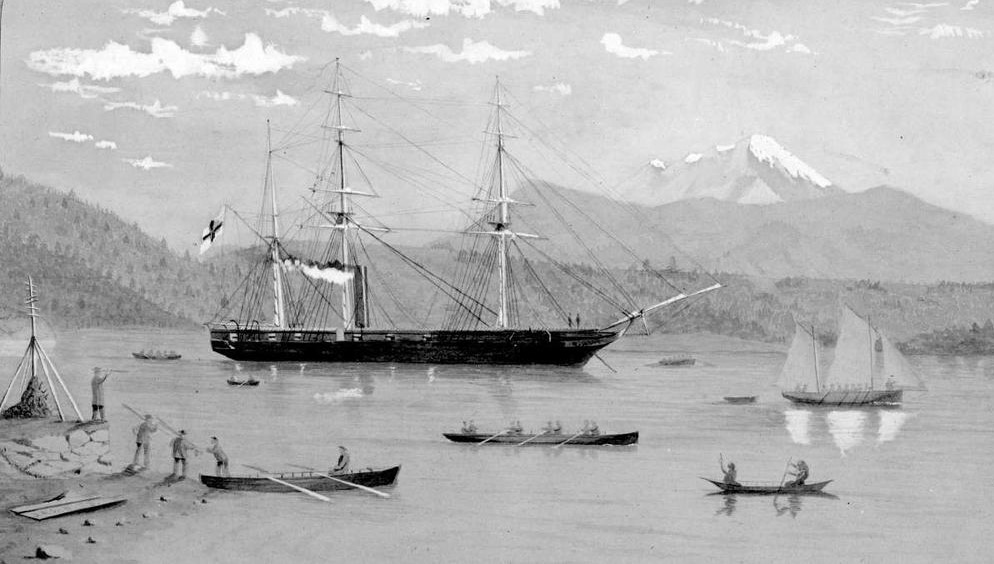

That fall, after letting the Americans do the dirty work, the British ventured out of their fort at Victoria, travelled upriver and proclaimed the crown colony of “British Columbia”. Today the crown still claims 95 per cent of the land, which it leases out to corporations for resource extraction. About five per cent is private property. 0.4 per cent is “Indian Reserves”.

The bloodshed of the 1850s, and deliberate spreading of smallpox in the 1860s, opened the door for land theft, human suffering and ecosystem disruption on a scale that is difficult to comprehend. Until we reckon with that history, B.C. can only get so far in solving the problems we face today.

Path one: education

Ask most British Columbians what happened in the Fraser Canyon in 1858 – or Victoria in 1862 or Quesnel in 1864 – and they draw a blank. How many longhouse villages were razed by British cannon fire? I count at least thirteen. Unlike the U.S. which celebrates its wars of conquest against the tribes, B.C. relies on collective amnesia, ignorance and denial to sustain the legal fiction that these lands belong to the Crown.

One small step toward halting or undoing some of the harms inflicted by colonization is to learn how we ended up where we are. Because it’s largely not taught in school, we rely on media organizations, artists, oral and written history to fill in the blanks. Unions, faith groups and NGOs can all play an important role in using their platforms and resources to educate members.

One example is the free, 80-page booklet “Challenging Racist British Columbia,” offered by the University of Victoria and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives to mark the 150th anniversary of B.C. joining Canada as a province. Its bibliography is packed with primary sources and additional reading on our unique jurisdiction, built on what the authors call “the Pacific politics of white supremacy”. [3]

From the Kootenays to the Peace, every corner of this province bears the scars of ongoing colonization, so I suggest starting at a regional or local level to avoid becoming overwhelmed. Or you can work chronologically, branching off from this historical timeline assembled by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs.

For many non-Indigenous people this learning comes with feelings of disbelief, horror, grief or complicity. While it’s normal to want to talk about it with friends, it’s not fair to burden Indigenous people with requests for resources or emotional support. Coming to terms with this is work for newcomers, and descendants of settlers and immigrants, to do ourselves.

Path two: reducing harm

Since the discovery of coal on the West Coast in the 1830s and gold in 1851, corporate interests have been scheming ways to separate Indigenous people from their lands. The colony, its settlements and bureaucracy were all created to facilitate resource extraction. Once we understand that, the government’s genocidal policies toward Indigenous people have a grim logic.

From the Potlatch Ban and residential schools to the present-day fight over equal funding for health care for Indigenous children, undermining Indigenous governance, language, food security and families is a foundational priority for both Canada and British Columbia. “Our poverty is not an accident,” the late Secwepemc leader Arthur Manuel wrote. “It is intentional and systematic.” [4]

And every non-consensual clearcut, fish farm or pipeline deepens the harm. As the Nuxalk Nation wrote in a letter to the governments of Canada and B.C. last month: “Through your ‘authorization’ of the commercial extraction of our resources you are willingly, knowingly and deliberately inflicting on our People conditions of life that will ultimately bring about our physical destruction.”

“This massive land dispossession and resultant dependency is not only a humiliation and an instant impoverishment,” Manuel continues. “It has devastated our social, political, economic, cultural and spiritual life.”

Much of this devastation is inflicted day to day by our colonial bureaucracy: police, prosecutors and prisons, child apprehension, foster care. As we are learning, systemic racism pervades our health care system, schools and every institution that wields power over people’s lives. Decolonizing them starts with reducing their ability to do violence, to Indigenous people and other marginalized communities.

Sometimes we can defang or repurpose an institution. Sometimes the only answer is abolition, as Canada finally did in 1996 with Residential Schools. And sometimes the harm is so acute, we have to step between Indigenous people and the machinery of the state.

When it comes to conflicts over resources, we cannot keep letting Indigenous land defenders be swallowed up by the criminal system. Allies, especially white people, need to use their privilege to reduce harm to Indigenous lands and people.

Path three: healing and rebuilding

Indigenous people have continuously resisted occupation, assimilation and genocide since long before B.C. became a province. The reason we can talk about decolonization today is because colonization never fully succeeded.

The Potlatch Ban drove Indigenous systems of government underground for 66 years. It did not succeed in destroying them. All over B.C., Big Houses and feast halls, hereditary systems, house groups and potlatch societies are now being rebuilt. Indigenous governments, not Indian Act band councils, are reviving and asserting their own laws.

People are reclaiming languages and art forms at the same time. And many nations have built healing centres and programs to reconnect people with their lands and cultures. All these efforts deserve support, especially from the corporations, wealthy families and governments that have taken so much wealth from Indigenous territories.

In 2018 the B.C. government committed $17 million per year to support Indigenous language programs. At the same time the province spent $13 million on police to force the Coastal Gaslink pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory, and millions more battling the Squamish Nation in court to uphold its Trans Mountain pipeline approval.

One day I hope the B.C. public spends far more of our tax dollars supporting Indigenous cultural revitalization, and no money at all violating or denying Indigenous rights. In the meantime any individual, foundation or organization with a budget can support language, healing, land-based learning and other Indigenous-led projects in every corner of the province. You can think of it as rent.

It’s also worth developing a working understanding of the layers of Indigenous government in your part of the world. The same way you would respect the B.C. fishing regulations or the whistle of a traffic cop, it’s important to recognize and comply with Indigenous travel restrictions, harvest limits, licencing, and other expressions of Indigenous sovereignty.

Path four: reimagining B.C.

I don’t know what this part of the world will be called in 150 years, but I would bet it’s not “British Columbia”. The eventual death of Queen Elizabeth II is going to open a conversation in Canada about our ties to the monarchy and by extension, the institution of the Crown that wields so much power in B.C.

The B.C. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, passed unanimously by MLAs in 2019, provides a framework for updating provincial laws and statutes to respect Indigenous rights and title. In theory it introduces the requirement of Free, Prior and Informed Consent for development or resource extraction on Indigenous territories.

In practice, it’s clear the government is still deeply invested in a paternalistic model of colonial land management. It will take many more years of lawsuits, blockades, and political and cultural transformation to loosen the grip of the Crown on these lands and resources.

One thing I would ask British Columbians is how well it’s actually working for them to have corporations call the shots on 95 per cent of the landbase. Whether it’s forestry or fishing, mining or gas, most of our communities are at the mercy of faraway investors. Transferring that authority back to Indigenous nations would almost certainly lead to more sustainable local economies, and better protection of biodiversity.

When it comes to real estate, housing and cities, no single project gives me more hope than Sen̓áḵw. While the Squamish Nation builds 6,000 zero emissions homes, mostly rental, on a sliver of reserve land in Kitsilano, Vancouver City Hall can barely approve a 35-unit apartment building. What could Indigenous nations build with more than 0.4 per cent of the land base?

As we spiral deeper into the climate emergency, it’s becoming clear that our colonial bureaucracy is not equipped or willing to challenge fossil fuel extraction. But there are other economic models and systems of government that predate British Columbia. Relinquishing the Crown’s claim on the land, and ceding power back to Indigenous nations, might be our best hope of surviving the next century.

Justice and decency

The crises that define British Columbians’ lives in 2021 – the ongoing pandemic, the poisoned drug supply, lack of housing, ecosystem collapse, rising emissions – these are not natural or inevitable. They are the result of policy choices within an economic system driven by profit. And in B.C. all of that is built on a foundation of ongoing violence, racism and theft.

It’s time to question that system and where it has brought us. In the first part of this series I laid out what Dogwood means by “decarbonize,” and why our organization is committing itself to halting fossil fuel expansion and doing everything we can to rapidly cut emissions. At the same time, our province needs to decolonize. In fact, one is not possible without the other.

The good news is you can help create the conditions for decolonization in many different ways, as an individual or in the groups you belong to. You can support Indigenous communities working to revitalize their languages and cultures. You can do battle with different tentacles of the colonial machine. If you don’t know where to start, you can read or watch videos (see below).

The hard part is forcing the Crown to actually divest itself of power, land, resources and money. But it can be done. After many decades of struggle, the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s 2014 Supreme Court victory recovered 1,700 square kilometres of “Crown land” claimed by the colony in 1858. Our challenge is to scale up and accelerate that work through focused legal and political action.

As Art Manuel wrote, “travelling along the path to decolonization will take courage for Canadians. But once you begin, I think you will find the route is not complicated and the only guide you will need is a sense of justice and decency.”

Manuel insisted on the human right of all people, including settlers, to call these lands home and have their economic and cultural needs met. No deportations required. “I promise you again that this does not have to be a painful process,” he wrote. “It can be a liberation for you as well as for us.”

References:

[1] Marshall, Daniel. Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado. Ronsdale Press, 2018

[2] Wunderman, Eva. Canyon War: the Untold Story. Available on YouTube. Wunderman Film, 2009

[3] Nick XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton, Denise Fong, Fran Morrison, Christine O’Bonsawin, Maryka Omatsu, John Price, Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra. Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting. University of Victoria / Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (BC Office), 2021

[4] Manual, Arthur. The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering the Land, Rebuilding the Economy. James Lorimer and Company, 2017

Thank you

Thank you for this insightful and important article Kai. We have to get this taught in schools! How can I post this on facebook?

It is terrible how the natives were treated but colonization has hurt ALL Canadians. Resources should be developed for the benefit of all Canadians and colonization is a hindrance to that end.

Decolonial strategies will have to be different based on demographics, since colonization has hurt different groups in different ways. Not all Indigenous groups were/are effected in the same way, and certainly White, Asian, Black, and Latinx Canadians feel colonization differently than Indigenous groups.

For example, my neighborhood has good water. My parents and I do not need (ethnic-based) therapeutic practices to be publicly facilitated for recovering from systematic intergenerational separation from forced residential schools. And some Indigenous groups need public powers to get out of their way so they can continue to form their own education systems, communal currencies, and economies. Whereas my White group needs reform to schools.

In short, my spheres, though comprising of people with different skin colors, all share certain conditions, and need a lot less public and autonomous improvements to living standards and agentic modes of living.

Equity, not equality.

Its good to notice how colonization hurts everyone (even ruling class, if you are counting their spiritual mobility).

But make sure to notice how utterly different colonization and its apparatuses work on different groups. If it deployed one mechanism on all groups, it would have been disarmed easily. It uses many mechanisms and interlocks with many other systems and power orders.